|

Lying just in the shadow of Snaefell mountain are the remains and reminders of what was once the scene of a terrible disaster. Off the beaten track, the scars from the days of mining at the top end of the Snaefell Valley lie forgotten, to all, but those who dare to brave the slopes to the old mine. The site is located about two and a half miles to the north west of Laxey Mine and at an altitude of one thousand feet above sea level, is the highest major mine on the Island.

Mining commenced about 1856 after outcrops of ore had been discovered in the bed of a stream which led to the eventual sinking of the main shaft. A second smaller shaft would have compared to that of a winze and stepped down to connect with the 25 fathom level. The workings were mainly above the 100 fathom level and comprised of six levels of around 100 fathoms in length but drivings on the 100, 130, 141 and the 171 had reached a distance of 500 fathoms before good ore ground was found. The final depth of the mine was 171 fathoms (1026 feet) The mine was not profitable and closed in 1908 due to a rock fall in the shaft. Work recommenced in the fifties when the spoil heaps were re-worked using new methods to refine the waste by flotation. A level under the mountain was re timbered but abandoned with no mining ever taking place.

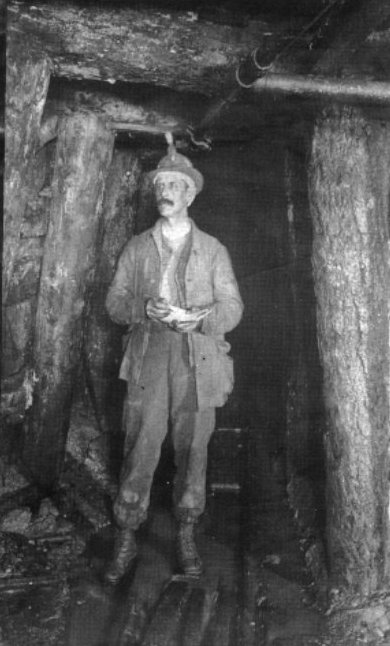

Like Laxey, The workings were kept dry with pumps driven by a water wheel although it is not known how many stages of pumping there were. The shaft was divided into three compartments for the purpose of pumping, climbing and the raising of ore as was the case of most mines. Compressed air was used for drilling at Snaefell and the two air pipes shared the same section of shaft as the rising main from the pumps. The mine was kept in good condition as was the report from captain Reddicliffe on Wednesday the 5th of May 1897 and again the mine was inspected on the 7th by the assistant To H M Inspector of Mines Mr Williams. He reported in writing that 'the ventilation was very good' with particular attention being paid to explosives, ladder ways, fencing and machinery, the mine was in fact given 'a clean bill of health'.

On the morning of Monday the 10th of May, a little after 6 a.m., the morning shift of thirty five men descended into the shaft. Shortly afterwards, several men came to the surface in an exhausted condition stating that the mine was full of foul gas. Captain Kewley immediately sent for assistance from Laxey before starting a descent of the shaft to assess the situation. On his descent, he met several men 'dead beat' trying to make their way up the ladder and fighting for breath. Between the 45 and 60 fathom level he found others, still alive but quite unconscious. Immediately, Captain Kewley had holes punched in the air pipes with a view of improving the ventilation in the shaft which did give some relief. The work of rescue continued with great difficulty until five o clock in the afternoon when James Kneale, the last survivor was brought to the surface. By now, the rescuers were thoroughly exhausted and Captain Kewley himself had made no less than ten journeys. During the evening, Mr Williams, who was still on the Island and by now, on hearing the news, had returned to the mine and immediately set about organizing a further rescue attempt. Mr Williams and a miner named Frederick Christian descended to the 100 fathom level passing three bodies at the 74 fathom level and and more bodies blocking the ladder way at the 100 fathom level. They decided to proceed no further as their strength was failing and so made their way up the shaft where they met the rest of the rescue party at the 60 fathom level who also complained of weakness. With no possibility of further rescue, the grim task of recovery commenced on the 12th and three bodies had been brought to surface by eleven o clock in the evening. The work continued the next day when ten bodies had been sent up and it was a week later before a party of volunteers recovered five more bodies from the 115 fathom level. Proceeding to the 130 fathom level, one miner knelt down and held a lit candle below the platform which immediately went out indicating the absence of oxygen. Mr Williams sent for bottles of water to brought down and on receiving them, descended below the platform and proceeded to pour out the water, as they drained , the poisonous gas replaced the liquid and the bottles were corked. On collecting a third 'air' sample, Mr Williams instantly became unconscious but was fortunately secured to a rope and was hauled to safety. Mr Williams mouth was held open to a hole in the air pipe to revive him.

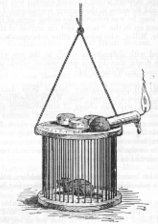

Mr Williams, Captain Kewley and Mr Jones Descended to the 100 fathom level and found two doors open, these were then closed to help ventilation at the lower levels. On the Saturday morning, tests with the mice showed that there was little change meaning that the door on the 130 level was open allowing air going down the shaft to pass through this level. A further descent was made by a party of men who lowered a tame rat and candle to the point where the poor miner lay dead, The light went out and the animal was left for five minutes or so but when brought up was found to be alive. The air was tested daily and and on the 17th of June it was finally considered safe enough to descend to the 130 level. A party of men went down and recovered the last body, that of Robert Kelly.

|

|

|||

|

||||

|

That

afternoon, a party of volunteers from Foxdale descended to the

130 level where Mr Williams had become unconscious and reported

seeing a body some ten feet below. A mouse was put into a cage,

made from it's revolving tread wheel and a candle attached to

the top. A descent was made to the 155 level and a test was made

with the mouse at each platform. On arriving at the bottom of

the fourth ladder, the cage was lowered and the candle went out,

it could be seen that the little animal was distressed and was

immediately pulled up to recover. After

some days, a test made from the surface showed that the level of

bad air had gone down and concluded that the ventilation doors

in the levels were open and not shut as previously thought.

That

afternoon, a party of volunteers from Foxdale descended to the

130 level where Mr Williams had become unconscious and reported

seeing a body some ten feet below. A mouse was put into a cage,

made from it's revolving tread wheel and a candle attached to

the top. A descent was made to the 155 level and a test was made

with the mouse at each platform. On arriving at the bottom of

the fourth ladder, the cage was lowered and the candle went out,

it could be seen that the little animal was distressed and was

immediately pulled up to recover. After

some days, a test made from the surface showed that the level of

bad air had gone down and concluded that the ventilation doors

in the levels were open and not shut as previously thought.